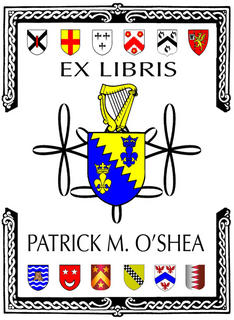

Ex Libris

Heraldry has always held a fascination for me. Perhaps it is the atmosphere of aristocracy that it creates. Perhaps it is the fact that true heraldry follows a set of rules and employs specific terminology (with most terms in Norman French), ensuring that the "common folk" don't quite understand its intricacies. Or perhaps it is the aesthetic appeal of a symbolic language that is at once beautiful and capable of transmitting a considerable amount of genealogical and other familial information.

Heraldry has always held a fascination for me. Perhaps it is the atmosphere of aristocracy that it creates. Perhaps it is the fact that true heraldry follows a set of rules and employs specific terminology (with most terms in Norman French), ensuring that the "common folk" don't quite understand its intricacies. Or perhaps it is the aesthetic appeal of a symbolic language that is at once beautiful and capable of transmitting a considerable amount of genealogical and other familial information.My early fascination with heraldry led me to the American College of Heraldry, and its then-president, the late Dr. David P. Johnson, who had been involved with this non-profit organization since its founding in 1972. The ACH, filling the vacuum left by the lack of an official heraldic authority in the United States, has done much over the years to help those wishing to assume arms in America, avoiding many errors and poor design. The ACH continues today, and I am now most honored to serve on its Board of Governors.

What is the point of a personal coat of arms? Well, obviously, I'm not about to ride out with a shield and lance in hand, so there isn't much need to identify myself in spite of a suit of chain mail or plate armor. However, the value of a symbolic identification system such as heraldry has proven extraordinarily consistent, with stationery, silver, and many other personal items. Establishing or reinstating a familial heraldic tradition remains attractive for aesthetic as well as pragmatic reasons, as evidenced by the continued upsurge in registrations of new arms by the ACH, under the capable leadership of its present Executive Director, David Wooten.

As an academic and avowed book pack rat, I must admit that one of my favorite uses of heraldry is the heraldic bookplate. Bookplates date to the Middle Ages, when hand-copied books were items of considerable value. Often, these were commissioned by wealthy noblemen, and the coats of arms of the patron in question were lavishly illustrated at the beginning of the volume.

As printing made books more available, the expanding middle class sought to acquire the marks of nobility, and these included both books and coats of arms. The marriage of the two was thus inevitable among commoners as well as nobles, and the precedent set has continued to the present, producing countless works of identifying heraldic art for the libraries of those bearing arms.

Frequently, bookplates employ the Latin formula, "ex libris" or "from the library of" plus the name of the owner. Of course, they might also have this formula in the vernacular, or omit it and simply use the name of the armiger. Historically, black and white versions are most common (often employing the common system of "hatching" or the use of lined or dotted patterns to indicate coloration). However, with the cost of color printing decreasing in recent times, color bookplates are increasingly common.

The present version of my own bookplate (above) is a recent revision of some earlier designs. Central to the bookplate are the arms and crest (gold harp) registered by the American College of Heraldry for my great-grandfather, Michael Joseph O'Shea (1889-1971), and thus pertaining to all of his descendants. These are depicted on a simple knot work background, with knot work borders to lend a Celtic flavor to the plate.

I chose to omit the motto, which is a less permanent feature of armorial achievements, and which may be changed by branches of families. In the case of this particular branch of O'Sheas, the motto recorded is QUAERITE VERITATEM (Seek Ye The Truth), a variation on the historic motto of the 1381 grant of arms to Odoneus O'Shee of Tipperary, VINCIT VERITAS (Truth Conquers). The O'Sheas, as a clan, are also said to have the motto, in Irish, Eala Dubh Uibh Rathach Abu! (Victory to the Black Swan of Iveragh!). The black swan was the totem animal of the O'Sheas.

Along the top edge are arms connected to my paternal ancestry, from left to right: (De) Wayland, Burgh (Burke), Smithwick, White, Maunsell, and Gabbett. Similarly, the bottom edge features arms from my maternal ancestry: Bilodeau, Gamache, d'Aillebout, Menteith of Kerse, De Marle, and Hotman.

Thanks to modern technology, these are conveniently printed on inkjet shipping labels (4" x 3.3"), and easily applied to the inside covers or blank front pages of books. And while this is certainly less impressive than a hand-painted armorial achievement on a vellum page of a hand-copied manuscript, it is a direct descendant of that ancient tradition.

Admittedly, not everybody will want to become a "heraldry geek." And, there are those who connect an interest in heraldry with role-playing and assumed fictional personas (the Society for Creative Anachronism). But I honestly believe that heraldry retains a value in the real, modern world. Yes, there are perhaps more efficient ways of identifying ownership of something, and there are modes of information storage and transmission that carry exponentially more data. And yet, there is an intrinsic value in a thing of beauty, particularly if it serves a function in addition to its aesthetic worth.

And besides, how many other hobbies can you have where you get to use Norman French?

-PMOS

1 Comments:

This comment has been removed by the author.

Post a Comment

<< Home